Important

The Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines were released in 2024. They incorporate many of the concepts (and more) from our tapering strategies, presented in a manner understandable to medical providers. You can purchase the guidelines here.

Introduction

Benzodiazepines, a class of medication known as anxiolytics, are listed as Schedule IV controlled substances. They are often prescribed for conditions such as anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and alcohol withdrawal, but are also given for a vast array of off-label uses such as restless leg syndrome, muscle spasms, tinnitus, dementia, mania, and akathisia. Commonly prescribed benzodiazepines include Klonopin (clonazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), Xanax (alprazolam), Valium (diazepam), Onfi (clobazam), Tranxene (clorazepate dipotassium) and Librium (chlordiazepoxide).

Most prescribing guidelines recommend against using benzodiazepines for more than two to four weeks consecutively. While estimates vary, and we don’t know the exact number, a large percentage of patients prescribed benzodiazepines long-term (more than two to four weeks) will develop physical dependence and have problems safely stopping the medications. No matter how much they wish to withdraw, many experience debilitating mental and physical withdrawal effects.

It cannot be predicted at the time patients start or stop a benzodiazepine who will be able to successfully withdraw from the medication without serious complications. Still, cessation can become a lengthy, life-altering process for those with complex withdrawals. For this reason, doctors and patients must be educated about the available methods of tapering. The methods discussed below have been developed through clinical experience, research, and the input of patients who have successfully completed a benzodiazepine taper.

An Important Note About Physical Dependence Versus Addiction

Prescribed physical dependence is not addiction. Misdiagnosis and treating physical dependence as addiction has led to large amounts of patient harm through imposing dangerous forced or over-rapid cessation. More information can be found at:

FDA guidance is available to help distinguish between physical dependence, addiction, and abuse. It states:

Physical dependence is not synonymous with addiction; a patient may be physically dependent on a drug without having an addiction to the drug. Similarly, abuse is not synonymous with addiction. Tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal are all expected biological phenomena that are the consequences of chronic treatment with certain drugs. These phenomena by themselves do not indicate a state of addiction.

Additionally, the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) states:

“Dependence” has been easily confused with the term “addiction” when, in fact, the tolerance and withdrawal that previously defined dependence are actually very normal responses to prescribed medications that affect the central nervous system and do not necessarily indicate the presence of an addiction.

How Benzodiazepine Use Alters the Body

The underlying physical changes resulting in benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal are unknown. One hypothesis is that since benzodiazepines work by enhancing the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) at the GABA-A receptor, long-term benzodiazepine use may down-regulate GABA receptors while discontinuation may, with time, upregulate them. GABA receptors are located throughout the body and have many roles. They are an essential part of the body’s central nervous system and stress response.

Problems with Common Prescriber Cessation Methods

“Slow” Tapers That Aren’t

One standard method (not recommended) is instructing patients to reduce their dose by one-quarter weekly. With this method, the patient would finish tapering in several weeks. While some prescribers may view this as a gradual reduction, most experienced researchers, physicians, patients, and prescribing guidelines consider these tapers too rapid. A four-week taper is usually not enough time for the body to adjust. This rapid tapering method was found in one study to be ineffective for at least 32% to 42% of patients who were prescribed benzodiazepines long-term (that is, they failed to achieve a drug-free state). Some 90% experienced withdrawal symptoms.

There are many instances of patients developing a protracted withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) from rapid tapers of this nature. This withdrawal syndrome can last anywhere from eighteen to twenty-four months, or in some cases much longer, up to many years. A slower, more-gradual dose reduction can lessen the severity of withdrawal and the risk of PAWS. Beyond protracted withdrawal risks, patients are also at risk of seizures and sometimes even death from over-rapid tapers.

Physically dependent patients may be so severely sensitized to benzodiazepines that even minute fluctations in dosage can cause terrible suffering. Since pills are scored only in halves (with many not scored at all), and since even breaking a pill in half is inaccurate, attempting to split pills to distribute the medication into four equal parts evenly is doomed to producing uneven doses and can exacerbate the severity and fluctuation of symptoms throughout a taper.

Skipping Doses

Another commonly prescribed tapering method requires patients to decrease one of their daily doses throughout the week, over the course of several weeks, until all doses have been removed. This protocol presents problems similar to the one-quarter-dose reduction per week method. In our observations of online support groups representing over a hundred thousand patients, Benzodiazepine Information Coalition has seen this “reduce one of your daily doses a week” approach cause a cluster of disabling mental and physical symptoms that can persist for months or years. One reason may be that, compared to a steady, careful, consistent decline of the drug, skipping doses or leaving longer time gaps between them leads to greater fluctuations—peaks and valleys in drug serum levels—sending patients in and out of withdrawal and often resulting in unnecessary pain and suffering.

Tapering Styles

The delivery styles for safe cessation can be either dry (tablet) or liquid. There are also two reduction styles: “cut and hold” or “micro-taper.” As for tapering approaches, there are many effective ones for coming off benzodiazepines. Unfortunately, most benzodiazepines do not come in forms or dosages compatible with easy cessation, so nearly all require manipulating the dosage through some method, whether cutting with a scale, compounding, or using liquid.

Cut and Hold

A “cut and hold” method involves reducing the current dose by a set amount (not more than 5% to 10% of the current dose) and holding the new dose until symptoms subside. It often takes several weeks after a reduction for the nervous system to settle.

Micro-taper

Online support communities have developed different systems of “micro-tapering” to help reduce medication evenly throughout a taper to lessen the chance of withdrawal symptoms. Micro-tapering requires small, daily microgram reductions that add up to not more than a 5% to 10% overall reduction from the current dose each month.

Daily micro-reductions may help prevent some physical and mental turmoil that larger weekly reductions can create for those very sensitive. Keeping track of dose reductions during a micro-taper usually requires a daily log or spreadsheet.

About Dry Tapers

This is a popular method due to its convenience and because some may find it initially more straightforward than other methods. It involves using a pill cutter or scale and cutting or shaving off pieces of a pill to make reductions. There are various methods for dry-tapering, including the cut-and-hold method (cutting a pill to remove milligram amounts periodically, perhaps once a month, then holding that dose until withdrawal symptoms stabilize) and micro-tapering (removing very small microgram amounts more frequently, perhaps every day, adjusting the rate according to symptoms).

The Ashton Manual

The Ashton Manual, written by the late psychopharmacologist Heather Ashton, presents the most well-known and respected withdrawal method in the benzodiazepine community. Dr. Ashton ran a benzodiazepine-withdrawal clinic in the U.K. for fourteen years, which reported a 90% success rate. Her protocol recommended using diazepam for tapering. Its long half-life of up to 200 hours can help prevent secondary issues such as interdose withdrawal (symptoms that develop between doses). In addition, diazepam comes in smaller doses than the newer, shorter-acting benzodiazepines, making it more suitable for a gradual taper.

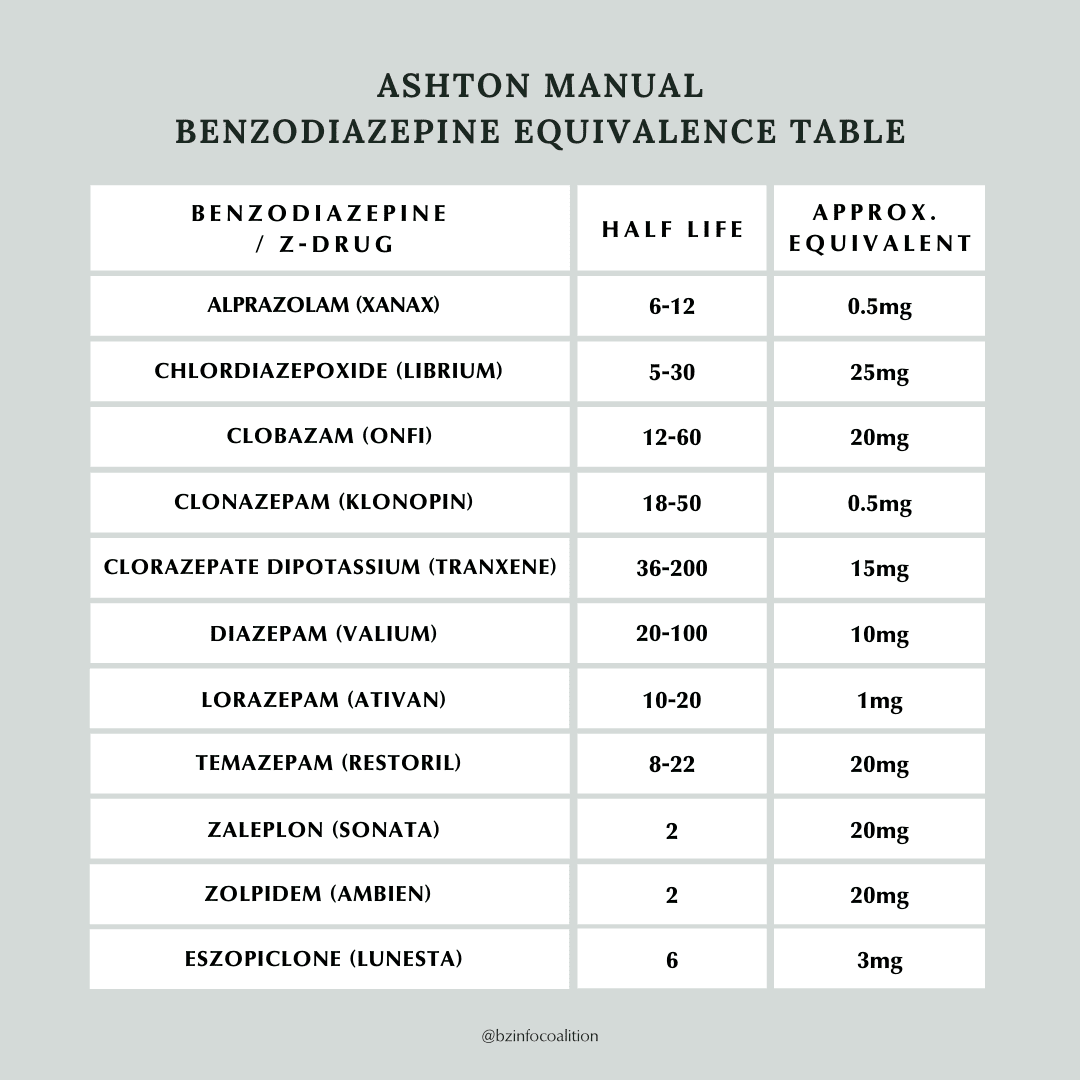

In contrast to diazepam, clonazepam has a medium half-life, with the smallest available dose of 0.125 mg, while alprazolam has a short half-life, with the smallest available dose of 0.25 mg. These may seem like “small doses,” but their approximate equivalence to diazepam (0.125 mg of clonazepam is equivalent to 2.5 mg of diazepam, and 0.25 mg of alprazolam is equivalent to 5.0 mg of diazepam), they are not so small. Discontinuing a benzodiazepine from these doses is not recommended, so the pills would need to be reduced by an amount smaller than half or a quarter of the lowest manufactured doses available, which cannot be done with any accuracy by simply breaking a pill. (For a discussion on the many problems arising from available dosage sizes, see Why Currently Available Benzodiazepine Doses Prevent Safe Withdrawal.)

Regarding tapering rate or speed, the Ashton Manual recommends that, on average, a taper will take some ten months or longer (sometimes quite a bit longer), depending on a patient’s starting dose and individual response. Dr. Ashton clarified that it is important to allow patients to dictate the rate and pace of their taper depending on their physiological response to dose reduction. If symptoms are severe or disabling, a taper can be suspended for a few weeks until symptoms subside. Oftentimes this resolves the problem, and patients can resume tapering. It is not uncommon for benzodiazepine tapers to take significantly longer than patients (or prescribers) might expect.

In the years since Dr. Ashton suggested using diazepam for tapering due to its long half-life, other guidelines have recommended staying on the originally prescribed benzodiazepine if withdrawal symptoms are tolerable. There are a few reasons: As with any new medication introduced, switching to diazepam can entail the risk of an adverse reaction, as some people may not respond well to the new drug. Additionally, many people have reported that the tapering rate suggested by the Ashton Manual is too fast for them and its scheduled reductions are too large to adjust to. What’s more, when a person is switching from a shorter half-life benzodiazepine to diazepam, the stepwise schedule Dr. Ashton suggests can add weeks to the process before a taper can even begin (or resume)—a delay that adds time to what is already perceived to be a long and painful project. And finally, because of the complex nature of benzodiazepine withdrawal, it can be difficult when switching to diazepam to know if a person’s symptoms are due to an adverse reaction to the new medication or the neuroadaptations caused by long-term exposure to benzodiazepines in general.

For more information, watch Dr. Ashton speak about her Manual:

Tapering Strips

A newcomer to the benzodiazepine-tapering market is Tapering Strips, developed by Dr. Peter Groot in the Netherlands. These strips, which can be ordered in advance, offer gradual reductions and adjust tapering rates according to patients’ needs. The benzodiazepines offered via Tapering Strips are Ativan (lorazepam), Valium (diazepam), Klonopin (clonazepam), Serax (oxazepam), Restoril (temazepam), and Imovane (zopiclon). Because Tapering Strips are a Netherlands-based operation, availability varies by country. The company’s website states that the strips can be shipped worldwide to those with a prescription within an expected one-week delivery time. They also note that they cannot ship anything listed on the Netherlands’ Opium Law list outside of the Netherlands, which includes most benzodiazepines, so access may be restricted to the Netherlands.

For more information, listen to Dr. Groot speaking about his Tapering Strips:

Dry Micro-taper with Scale

Some patients micro-taper using a scale by removing a small amount, perhaps between 0.001 and 0.003 grams, every day or every few days. This method can initially be intimidating to many, and a few different approaches exist. Videos and resources are available in online support groups explaining the various approaches. Some patients who find the rate of reduction used in the Ashton Manual to be intolerable but are not able, for whatever reason, to use a liquid approach choose this method.

Liquid Tapering Methods

Liquid tapering enables patients to decrease their doses gradually and at a lower reduction rate and frequency than other methods. It also allows for dosing multiple times a day, which can ease interdose withdrawal effects, and it allows patients to follow daily microtapers.

The reductions used in a microtaper are cumulative until the dose is small enough to stop (although the size of the reductions in milliliters, or the milligram-to-milliliter ratio of drug to liquid, can be easily adjusted to slow down the tapering rate if need be).

Manufacturer’s Oral Solution

In cases where medication is available from the manufacturer as an oral solution, this method allows a patient to make small reductions or implement a daily microtaper.

In one example, an oral diazepam solution (from Roxane Laboratories) is available in the U.S. as a 5 mg / 5 mL (1 mg per mL) solution. Using a 1-milliliter oral syringe, reductions can be measured from the daily dose as small as 0.05 mg to 0.10 mg every day or every three or more days. (How much they reduce depends on the individual responses, the existing dose, and the desired rate of reduction). For an even more dilute solution and smaller dose reductions, the manufacturer’s diazepam solution can also be safely combined with water.

For those who cannot tolerate the oral diazepam solution or cannot tolerate diazepam at all, a prescription for a liquid compound made from the patient’s original benzodiazepine can alternatively be used.

Compounding Pharmacies

To make an oral solution from a patient’s prescription, compounding pharmacists can combine suspending vehicles such as OraPlus with crushed pills or the stock powder form of most benzodiazepines. (Most compounding pharmacists have access to a database that allows them to choose the appropriate suspending agent for each specific benzodiazepine.) Compared to other methods, using a liquid compound can make it easier for patients to control their tapering rate and require less work (though compounding can be costly and not always covered by insurance). We recommend choosing a pharmacist associated with the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists or the Professional Association of Compounding Pharmacists.

Water / Milk Titration Method

One layperson-devised liquid tapering method is known in the online support community as “water titration” or “the discard method.” Some people use water titration because they can’t tolerate compounded liquids for some reason, such as intolerance to the suspending vehicle.

In the liquid titration approach, a pill is either crushed or allowed to disintegrate in a premeasured (in milliliters) amount of milk or water to create a suspension. Using an oral syringe, the patient removes an amount of liquid (measured in milliliters) from this suspension and discards it, ingesting the remainder. Holds are recommended should symptoms become intolerable.

One disadvantage to this method is that most medications are not water-soluble (meaning they are not fully dissolved in water), so the resulting liquid suspension must be shaken to distribute the medication fully.

Here is a video explaining one water titration method:

Another video explains a titration method using milk:

Tapering Strategies

Recommended Taper Rate

The general guideline is to not exceed a 5% to 10% reduction of the current dose every four weeks. One study found that a “tapering” method used by many physicians—to reduce a benzodiazepine dose by 25% a week—was ineffective for at least 32% to 42% (that is, they failed to get off the drug).

Conversion Rates for Benzodiazepines

For those who opt to switch from a shorter-acting to a longer-acting benzodiazepine to taper, one tricky aspect is calculating the conversion. Luckily, Dr. Heather Ashton created a guide of estimated conversions that worked well for the patients in her clinic. Unfortunately, her guide can vary significantly from other charts and individual physician opinions. Just as it is important to let patients determine their rate of reduction, it is best to let patients decide their optimal conversion dose. If they try a more-conservative conversion and feel underdosed or experience intolerable withdrawal symptoms, they should be allowed to increase their dose until they are comfortable before attempting a reduction. Unlike opiates, benzodiazepine equivalents are not studied or mandated by the FDA, and individual responses may differ.

Dosing Multiple Times per Day

Depending on the half-life of their particular benzodiazepine, many patients find it helpful to take a dose several times per day (while keeping their total daily amount the same). Patients who dose evenly and at regular intervals may be more likely to complete a successful benzodiazepine taper because they don’t experience peaks and valleys in drug serum levels throughout the day that may make discontinuation intolerable.

For example, some patients taking diazepam benefit from evenly dividing their doses and taking it two or three times a day; some on clonazepam benefit from dosing three or four times a day; and some taking lorazepam need to dose four or five times a day. Some patients on alprazolam require five or six daily doses to maintain steady serum levels. Where possible, all doses should remain as even as possible.

Medications to Alleviate Withdrawal Symptoms

Currently, no FDA-approved medications exist to alleviate the symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal. Add-on medications such as Neurontin (gabapentin), Lyrica (pregabalin), Catapres (clonidine), BuSpar (buspirone), and various antidepressants may be suggested but are not required to taper and can be counterproductive. There is little to no evidence for their effectiveness as withdrawal aids, and some may need long tapers to stop and create new adverse effects. The British National Formulary benzodiazepine guidance states: “The addition of beta-blockers, antidepressants, and antipsychotics should be avoided where possible.”

Benzodiazepine Information Coalition’s observations of the reports in online support groups, which represent over a hundred thousand patients, indicate that many people withdrawing from benzodiazepines develop multiple sensitivities to other medications, which in some cases seem to aggravate symptoms of withdrawal.

Conclusion

The most important thing in cessation of a benzodiazepine is patient safety. There is no perfect method guaranteed to prevent a painful withdrawal. Still, the methods mentioned here can lead many patients to a tolerable taper and maximize the patient’s chance for successful cessation and complete healing.

In some rare cases, a rapid withdrawal might be considered a lesser evil—for example, if the drug produces a paradoxical response, which happens very infrequently. While many patients who want to get off benzodiazepines have an understandable desire to withdraw from the medication as quickly as possible, rapid withdrawal is often the riskiest and most dangerous once signs of physical dependence are present.

Whether patients are working closely with a prescriber or withdrawing with limited assistance, they should taper at the most comfortable rate. No patient should ever be made to taper or forced off benzodiazepines against their will. As the methods here indicate, once a patient chooses to withdraw, there are many ways to accomplish that goal without relying on rapid tapers, oversized reductions, or cold turkeys.